THE WELFARE AND INCENTIVE EFFECTS OF JOB DISPLACEMENT INSURANCE

OUR AIMS

Labour markets in low-income countries face a pressing policy question: what are the welfare and employment impacts of expanding job-displacement insurance?

This is because:

- job loss is common and workers do not seem to fully insured against it (Meyer et al. 2021; Gerard & Naritomi 2021),

- expanding insurance can help address job search barriers and improve the allocation of talent (Abebe et al. 2021),

- expanding insurance can increase demand for labour market formality.

There is limited empirical evidence on the design of job-displacement insurance in low-income countries because mass lay-off events are hard to anticipate and difficult to study. There are no experimental papers that evaluate the impacts of offering different forms of support to workers who lose their job. This remains an open question of substantial policy interest both in Ethiopia and other low-income countries (Gerard, Imbert and Orkin 2020). This project implements an experiment to study the welfare and labour market impacts of expanding job-displacement insurance in Ethiopia.

Policy implications

The recent economic and social shock caused by the COVID-19 epidemic has emphasized the need to strengthen social protection and insurance for workers in low-income economies and has highlighted the evidence gap documenting promising strategies for expanding displacement insurance (Gerard, Imbert, Orkin, 2020). Moreover, the “unconditional” income support scheme that we will evaluate is a promising policy for LMICs (Gerard and Naritomi, 2021), but it has never been implemented in practice.

Expanding job-displacement insurance in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is a policy priority. First, structural transformation in these countries often generates new jobs that are formal but quite unstable. Understanding how to protect workers in these new jobs is thus increasingly important. Second, jobseekers often misallocate their talents and skills due to liquidity constraints (Abebe et al., 2021). Insurance provision can support displaced workers in the search for better matches for their talents and skills. Third, governments in LMICs are keen to promote formal employment. Job-displacement insurance is a key benefit of formal employment and can thus be an important lever to attract workers to the formal sector (Bosch and Esteban-Pretel, 2015; Cirelli, Espino and Sánchez, 2021).

ABOUT THE PROJECT

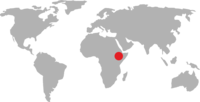

Ethiopia lost preferential access to the US market in early 2022 due to the ongoing conflict in the north of the country. This hit exporting firms in the garment sector hard and led to mass-layoffs of garment workers. The project is set in Hawassa Industrial Park, Ethiopia, where many firms had to resort to mass lay-offs as demand for their good plummeted. Researchers sampled 1410 young women who were laid off by a ready-made garment manufacturer in August 2022

The researchers evaluate the impacts of offering to the laid-off group:

- an “income support” scheme which pays 60 percent of the worker’s wage for 5 months, irrespective of employment status;

- a single lump-sum payment of the same present value as the income support scheme.

The project also included a control group of equal size to the other groups. The researchers also recruit a “still working” group of 400 workers employed at neighbouring firms in Hawassa Industrial Park who had not lost their job as a benchmark for the negative effects of job loss.

Through bi-monthly frequency surveys, the researchers study the impacts on consumption, well-being, job-search, employment outcomes, migration and demand for formality and job-displacement insurance. The comparison of the impacts of the two types of payment (lump-sum versus monthly) will shed light on saving and liquidity constraints. If discharged workers face lump-sum expenses and are liquidity constrained, the lump-sum payment will have stronger impacts. On the other hand, if saving is costly or risky or workers are present-biased (Gerard and Naritomi, 2021), the regular payment will have stronger impacts. Documenting these constraints can inform the design of additional interventions specifically targeted to relax these barriers. The data collected on policy preferences (i.e., whether individuals prefer the lump-sum or the monthly payment) will provide information on selection into different insurance products and on whether this selection is adverse or efficiency-enhancing.

By documenting the relative evolution of consumption and wellbeing among the treatment groups, the project will also provide direct evidence on the existence and scale of a social protection gap. This will help to inform the design of a broad class of policies aiming to improve social protection.

The lessons learned will be relevant beyond the context of the study. First, the level of severance pay available to our workers is close to the median level available in LMICs (Holzman et al., 2011). Second, industrial parks and garment manufacturing employment are common avenues for wage work in LMICs. Third, the two interventions can be implemented with low administration costs or capacity, as they do not condition payments on outcomes that are hard to verify.

RESULTS

Research ongoing, results to follow.